- Home

- Kristin Harmel

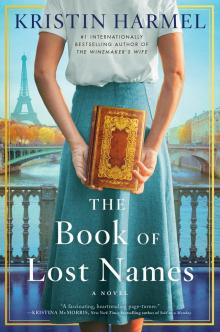

The Book of Lost Names

The Book of Lost Names Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

To my Swan Valley sisters—Wendy, Allison, Alyson, Emily, and Linda—who understand, as only writers and readers truly can, that books shape destiny.

And to librarians and booksellers everywhere, who ensure that the books with the power to change lives find their way into the hands of the people who need them most.

Chapter One

May 2005

It’s a Saturday morning, and I’m midway through my shift at the Winter Park Public Library when I see it.

The book I last laid eyes on more than six decades ago.

The book I believed had vanished forever.

The book that meant everything to me.

It’s staring out at me from a photograph in the New York Times, which someone has left open on the returns desk. The world goes silent as I reach for the newspaper, my hand trembling nearly as much as it did the last time I held the book. “It can’t be,” I whisper.

I gaze at the picture. A man in his seventies looks back at me, his snowy hair sparse and wispy, his eyes froglike behind bulbous glasses.

“Sixty Years After End of World War II, German Librarian Seeks to Reunite Looted Books with Rightful Owners,” declares the headline, and I want to cry out to the man in the image that I am the rightful owner of the book he’s holding, the faded leather-bound volume with the peeling bottom right corner and the gilded spine bearing the title Epitres et Evangiles. It belongs to me—and to Rémy, a man who died long ago, a man I vowed after the war to think of no more.

But he’s been in my thoughts this week anyhow, despite my best efforts. Tomorrow, the eighth of May, the world will celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of Victory in Europe Day. It’s impossible, with all the young newscasters speaking solemnly of the war as if they could conceivably understand it, not to think of Rémy, not to think of the time we spent together then, not to think of the people we saved and the way it all ended. Though my son tells me I’m blessed to have such a sharp mind in my old age, like many blessings this one is mixed.

Most days, I just long to forget.

I blink away the uninvited thoughts of Rémy and return my attention to the article. The man in the photo is Otto Kühn, a librarian from the Zentral- und Landesbibliothek in Berlin, who has made it his life’s mission to return books looted by the Nazis. There are apparently more than a million such books in his library’s collection alone, but the one he’s holding in the photo—my book—is the one he says keeps him up at night.

“This religious text,” Kühn has told the reporter, “is my favorite among the many mysteries that occupy our shelves. Published in Paris in 1732, it’s a very rare book, but that’s not what makes it extraordinary. It is unique because within it, we find an intriguing puzzle: some sort of code. To whom did it belong? What does the code mean? How did the Germans come to possess it during the war? These are the questions that haunt me.”

I feel tears in my eyes, tears that have no place there. I wipe them away, angry at myself for still being so emotional after all these years. “How nice it must be,” I say softly to Kühn’s picture, “to be haunted by questions rather than ghosts.”

“Um, Mrs. Abrams? Are you talking to that newspaper?”

I’m jolted out of the fog of my memory by the voice of Jenny Fish, the library’s assistant manager. She’s the type who complains about everything—and who seems to enjoy suggesting at every opportunity that since I’m eighty-six, I might want to think about retiring soon. She is always eyeing me suspiciously, as if she simply cannot believe that at my age, I’d still want to work here.

She doesn’t understand what it means to love books so passionately that you would die without them, that you would simply stop breathing, stop existing. It is quite beyond me, in fact, why she became a librarian in the first place.

“Yes, Jenny, indeed I am,” I reply, without looking up.

“Yes, well, you probably shouldn’t be doing that in front of library guests.” She says it without a trace of irony. “They might think you’re senile.” She does not have a sense of humor.

“Thank you, Jenny. Your advice is always so very helpful.”

She nods solemnly. It is also apparently beyond her comprehension that someone who looks like me—small, white-haired, grandmotherly—is capable of sarcasm.

Today, though, I have no time for her. All I can think about is the book. The book that held so many secrets. The book that was taken from me before I could learn whether it contained the one answer I so desperately needed.

And now, a mere plane flight away, there’s a man who holds the key to unlocking everything.

“Do I dare?” I murmur to the photo of Otto Kühn. I respond to my own question before doubt can creep in. “I must. I owe it to the children.”

“Mrs. Abrams?” It’s Jenny again, addressing me by my surname, though I’ve told her a thousand times to call me Eva, just as she addresses the younger librarians by their given names. But alas, I am nothing to her but an old lady. One’s reward for marching through the decades is a gradual process of erasure.

“Yes, Jenny?” I finally look up at her.

“Do you need to go home?” I suspect she says it with the expectation that I’ll decline. She’s smirking a bit, certain that she has asserted her superiority. “Perhaps gather yourself?”

So it gives me great pleasure to look her right in the eye, smile, and say, “Yes, Jenny, thank you ever so much. I think I’ll do just that.”

I grab the newspaper and go.

* * *

As soon as I arrive at my house—a cozy bungalow just a five-minute walk from the library—I log on to my computer.

Yes, I have a computer. And yes, I know how to use it. My son, Ben, has a bad habit of pronouncing computer terms slowly in my presence—in-ter-net and e-mail-ing—as if the whole concept of technology might be too much for me. I suppose I can’t blame him, not entirely. By the time Ben was born, the war was eight years past, and I’d left France—and the person I used to be—far behind. Ben knew me only as a librarian and housewife who sometimes stumbled over her English.

Somewhere along the way, he got the mistaken idea that I am a simple person. What would he say if he knew the truth?

It’s my fault for never telling him, for failing to correct the error. But when you grow comfortable hiding within a protective shell, it’s harder than one might expect to stand up and say, “Actually, folks, this is who I am.”

Perhaps I also feared that Ben’s father, my husband, Louis, would leave me if he realized I was something other than the person I wanted him to see. He left me anyhow—pancreatic cancer a decade ago—and though I’ve missed his companionship, I’ve also had the strange realization that I probably could have done without him much sooner.

I go to the website for Delta—habit, I suppose, since Louis traveled often for business and was part of the airline’s frequent-flier program. The prices are exorbitant, but I have plenty stashed away in savings. It’s just before noon, and there’s a flight that leaves three hours from now, and another leaving at 9:35 tonight, connecting in Amsterdam tomorrow, and landing in Berlin at 3:40 p.m. I click immediately and book the latter. There is something poetic about knowing I will arrive in Berlin sixty years to the day after the Germans signed an uncondi

tional surrender to the Allies in that very city.

A shiver runs through me, and I don’t know whether it’s fear or excitement.

I must pack, but before that, I’ll need to call Ben. He won’t understand, but perhaps it’s finally time for him to learn that his mother isn’t the person he always believed her to be.

Chapter Two

July 1942

The sky above the Sorbonne Library in Paris’s fifth arrondissement was gray and pregnant with rain, the air heavy and thick. Eva Traube stood just outside the main doors, cursing the humidity. She knew, even without consulting a mirror, that her dark, shoulder-length hair had already doubled in volume, making her look like a mushroom. Not that it made a difference; the only thing anyone would notice was the six-pointed yellow star stitched onto the left side of her cardigan. It erased all the other parts of her that mattered—her identity as a daughter, a friend, an Anglophile working toward her doctorate in English literature.

To so many in Paris now, she was nothing but a Jew.

She shuddered, feeling a sudden chill. The sky appeared foreboding, as if it knew something she didn’t. The shadows cast by the gathering clouds seemed to be the physical embodiment of the darkness that had fallen over the city itself.

Courage, her father would say, his French still rough around the edges, with the vestiges of a Polish accent. Cheer up. The Germans can only bother us if we let them.

But his optimism was unrealistic. The Germans were perfectly free to bother France’s Jews anytime they wanted to, whether Eva and her parents acquiesced or not.

She looked skyward again, considering. She had planned to walk home in order to avoid the Métro and the new regulations—Jews were to ride only in the last, sweltering, airless car—but if the skies opened up, perhaps she’d be better off belowground.

“Ah, mon petit rat de bibliothèque.” A deep voice just behind Eva jarred her from her thoughts. She knew who it was before she turned, for there was only one person she knew who used “my little book rat” as a pet name for her.

“Bonjour, Joseph,” she said stiffly. She could feel the heat creeping up her cheeks, and she was embarrassed by her attraction to him. Joseph Pelletier was one of the only other students in the English Department who wore the yellow star—though unlike her, he was only half Jewish and nonobservant. He was tall, his shoulders broad, his hair thick and dark, his eyes a pale blue. He looked like a film star, a sentiment she knew was shared by many of the girls in the department—even the Catholic ones, whose parents would never allow their daughters to be courted by a Jew. Not that Joseph seemed the type to court anyone. He was more likely to seduce you in a shadowy corner of the library and leave you swooning.

“You look awfully pensive, little one,” he said, smiling at Eva as he kissed her on both cheeks in greeting. His mother had known hers since before she was born, and he had a way of making her feel as if she were still the small child she’d been when she first met him, though she was now twenty-three to his twenty-six.

“Just wondering if it will rain,” she replied, inching away from him before he could notice that the physical contact was making her blush.

“Eva.” The way he said her name made her heart skip. When she dared look at him again, his eyes were full of something disquieting. “I’ve come looking for you.”

“What for?” For a split second, she hoped he would say, To invite you to dinner. But that was perfectly ridiculous. Where would they go, in any case? Everything was closed to people who wore the star.

He leaned in. “To warn you. There are rumors that something is brewing. A massive roundup, before Friday.” His breath was warm on her ear. “They have as many as twenty thousand foreign-born Jews on the list.”

“Twenty thousand? That’s impossible.”

“Impossible? No. My friends have very reliable sources.”

“Your friends?” Their eyes locked. She’d heard about the underground, of course, people working to undermine the Nazis here in Paris. Is that what he meant? Who else would know such a thing? “How can you be so sure they’re right?”

“How can you be sure they’re not? As a precaution, I think it’s best for you and your parents to go into hiding for the next few days.”

“Into hiding?” Her father was a typewriter repairman, her mother a part-time seamstress. They barely had the means to pay for their apartment, let alone a place to lie low. “Perhaps we should check into the Ritz, then?”

“It’s not a joke, Eva.”

“I dislike the Germans as much as you do, Joseph, but twenty thousand people? No, I don’t believe it.”

“Just be careful, little one.” It was at that moment that the sky opened up. Joseph was swept away with the rain, vanishing into the sea of blooming umbrellas on the fountain-flanked sidewalk leading away from the library.

Eva swore under her breath. Raindrops pelted the pavement, making it slick as oil in the late afternoon half-light, and as she dashed from the steps toward the rue des Écoles, she was drenched in an instant. She tried to pull her cardigan over her head to shield herself from the downpour, but doing so only meant that her star, as big as the palm of her hand, was now front and center.

“Dirty Jew,” a man muttered as he passed, his face hidden by his umbrella.

No, Eva wouldn’t be riding the Métro today. She took a deep breath and began to run toward the river, toward the soaring mass of Notre-Dame, toward home.

* * *

“How was the library today?” Eva’s father sat at the head of their small table while her mother, her hair wrapped in a faded handkerchief, her stout body swathed in a threadbare cotton dress, spooned watery potato soup into his bowl, and then into Eva’s. They had all gotten caught in the rain, and now their sweaters hung drying just inside the open window, the yellow stars facing them like three little soldiers all in a row, silently watching.

“It was fine.” Eva waited for her mother to sit before taking a small taste of the bland meal.

“I don’t know why you insist on continuing to go,” Eva’s mother said. She paused for a spoonful of soup and wrinkled her nose. “They’ll never allow you to get your degree.”

“Things will change, Mamusia. I know they will.”

“Your generation and its optimism.” Eva’s mother sighed.

“Eva is right, Faiga. The Germans can’t keep up these regulations forever. They make no sense.” Eva’s father smiled a smile they all knew was false.

“Thanks, Tatuś.” Eva and her parents still addressed each other with Polish terms of endearment, though Eva, born in Paris, had never set foot in her parents’ native country. “So how was your work today?”

Her father looked down at his soup. “Monsieur Goujon does not know how much longer he can continue paying me. We may have to…” His gaze flicked to Mamusia, then to Eva. “We may have to leave Paris. If I lose my job, there’s no other way for me to make a living here.”

Eva had known this moment was coming, but still it hit her like a punch to the gut. If they left Paris, she knew she would never return to the Sorbonne, would never complete the degree in English she had worked so hard for.

Her father’s employment had been in jeopardy for a long time, since the Germans started to systematically remove Jews from French society. His reputation as the best typewriter and mimeograph repairman in Paris had saved him for the time being, though he was no longer allowed to work inside any government offices. But Monsieur Goujon, his old supervisor, had taken pity on him and was paying him for off-the-books work, most of which he did at home. In fact, there were eleven typewriters in various stages of disassembly currently lined up in the parlor, indicating a long night of work ahead.

Eva took a long breath and dug deep for some hope. “Perhaps it would be for the best if we left, Tatuś.”

He blinked at her, and her mother went silent. “For the best, słoneczko?” Her father had always called her that, Polish for “little sun,” and she wondered if he saw the

bitter irony in it now, as she did. After all, what was the sun but a yellow star?

“You see, I ran into Joseph Pelletier today—”

“Oh, Joseph!” Her mother cut her off, placing her palms on her own cheeks like a smitten schoolgirl. “Such a handsome boy. Did he finally ask you for a date? I always hoped the two of you might end up together.”

“No, Mamusia, nothing like that.” Eva exchanged glances with her father. Fixing Eva up with a suitable young man seemed to occupy an absurd proportion of Mamusia’s thoughts, as if they weren’t in the middle of a war. “Actually, he sought me out to tell me something. He heard a rumor that as many as twenty thousand foreign-born Jews are to be rounded up sometime within the next few days.”

Eva’s mother frowned. “That’s ridiculous. What on earth would they do with twenty thousand of us?”

“That’s what I said.” Eva glanced at her father, who still hadn’t spoken. “Tatuś?”

“It’s certainly a frightening thing to hear,” he said after a long pause, his words slow and measured. “Though Joseph seems the type to embellish.”

“Surely not. He’s such a nice young man,” Eva’s mother said instantly.

“Faiga, he has made Eva upset, and for what? So that he can puff out his chest and show her that he’s well connected? A decent fellow shouldn’t feel the need to do that.” Tatuś turned back to Eva. “Słoneczko, I don’t want to ignore what Joseph said. And I agree there is something brewing. But I’ve heard at least a dozen rumors this month, and this is the most outrageous. Twenty thousand? It’s not possible.”

“Still, Tatuś, what if he’s right?”

In response, he rose from the table and returned a few seconds later with a small printed tract. He handed it to Eva, who skimmed it quickly. Take all necessary measures to hide… Fight the police… Seek to flee. “What is this?” she whispered as she handed it to her mother.

The Room on Rue Amélie

The Room on Rue Amélie The Winemaker's Wife

The Winemaker's Wife The Forest of Vanishing Stars

The Forest of Vanishing Stars The Book of Lost Names

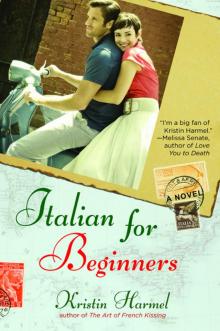

The Book of Lost Names Italian for Beginners

Italian for Beginners After

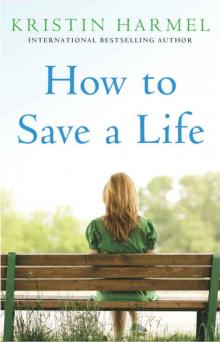

After How to Save a Life

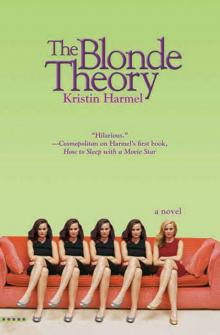

How to Save a Life The Blonde Theory

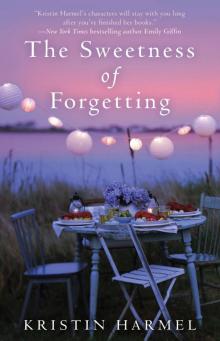

The Blonde Theory The Sweetness of Forgetting

The Sweetness of Forgetting When We Meet Again

When We Meet Again Life Intended (9781476754178)

Life Intended (9781476754178)