- Home

- Kristin Harmel

The Forest of Vanishing Stars

The Forest of Vanishing Stars Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

To Kathy Trocheck (Mary Kay Andrews), Kristy Woodson Harvey, Patti Callahan Henry, Mary Alice Monroe, Meg Walker, Shaun Hettinger, and all the members of our Friends & Fiction community. You filled a dark year with light, love, and friendship, and I will be forever grateful for all the ways you saved me.

CHAPTER ONE

1922

The old woman watched from the shadows outside Behaimstrasse 72, waiting for the lights inside to blink out. The apartment’s balcony dripped with crimson roses, and ivy climbed the iron rails, but the young couple who lived there—the power-hungry Siegfried Jüttner and his aloof wife, Alwine—weren’t the ones who tended the plants. That was left to their maid, for the nurturing of life was something only those with some goodness could do.

The old woman had been watching the Jüttners for nearly two years now, and she knew things about them, things that were important to the task she was about to undertake.

She knew, for example, that Herr Jüttner had been one of the first men in Berlin to join the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, a new political movement that was slowly gaining a foothold in the war-shattered country. She knew he’d been inspired to do so while on holiday in Munich nearly three years earlier, after seeing an angry young man named Adolf Hitler give a rousing speech in the Hofbräukeller. She knew that after hearing that speech, Herr Jüttner had walked twenty minutes back to the elegant Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten, had awoken his sleeping young wife, and had lain with her, though at first she had objected, for she had been dreaming of a young man she had once loved, a man who had died in the Great War.

The old woman knew, too, that the baby conceived on that autumn-scented Bavarian night, a girl the Jüttners had named Inge, had a birthmark in the shape of a dove on the inside of her left wrist.

She also knew that the girl’s second birthday was the following day, the sixth of July, 1922. And she knew, as surely as she knew that the bell-shaped buds of lily of the valley and the twilight petals of aconite could kill a man, that the girl must not be allowed to remain with the Jüttners.

That was why she had come.

The old woman, who was called Jerusza, had always known things other people didn’t. For example, she had known it the moment Frédéric Chopin had died in 1849, for she had awoken from a deep slumber, the notes of his “Revolutionary Étude” marching through her head in an aggrieved parade. She had felt the earth tremble upon the births of Marie Curie in 1867 and Albert Einstein in 1879. And on a sweltering late June day in 1914, two months after she had turned seventy-four, she had felt it deep in her jugular vein, weeks before the news reached her, that the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne had been felled by an assassin’s bullet, cracking the fragile balance of the world. She had known then that war was brewing, just as she knew it now. She could see it in the dark clouds that hulked on the horizon.

Jerusza’s mother, who had killed herself with a brew of poisons in 1860, used to tell her that the knowing of impossible things was a gift from God, passed down through maternal blood of only the most fortunate Jewish women. Jerusza, the last of a bloodline that had stretched for centuries, was certain at times that it was a curse instead, but whatever it was, it had been her burden all her life to follow the voices that echoed through the forests. The leaves whispered in the trees; the flowers told tales as old as time; the rivers rushed with news of places far away. If one listened closely enough, nature always spilled her secrets, which were, of course, the secrets of God. And now, it was God who had brought Jerusza here, to a fog-cloaked Berlin street corner, where she would be responsible for changing the fate of a child, and perhaps a piece of the world, too.

Jerusza had been alive for eighty-two years, nearly twice as long as the typical German lived. When people looked at her—if they bothered to look at all—they were visibly startled by her wizened features, her hands gnarled by decades of hard living. Most of the time, though, strangers simply ignored her, just as Siegfried and Alwine Jüttner had done each of the hundreds of times they had passed her on the street. Her age made her particularly invisible to those who cared most about appearance and power; they assumed she was useless to them, a waste of time, a waste of space. After all, surely a woman as old as she would be dead soon. But Jerusza, who had spent her whole life sustained by the plants and herbs in the darkest spots of the deepest forests, knew that she would live nearly twenty years more, to the age of 102, and that she would die on a spring Tuesday just after the last thaw of 1942.

The Jüttners’ maid, the timid daughter of a dead sailor, had gone home two hours before, and it was a few minutes past ten o’clock when the Jüttners finally turned off their lights. Jerusza exhaled. Darkness was her shield; it always had been. She squinted at the closed windows and could just make out the shape of the little girl’s infant bed in the room to the right, beyond pale custard curtains. She knew exactly where it was, had been into the room many times when the family wasn’t there. She had run her fingers along the pine rails, had felt the power splintering from the curves. Wood had memory, of course, and the first time Jerusza had touched the bed where the baby slept, she had been nearly overcome by a warm, white wash of light.

It was the same light that had brought her here from the forest two years earlier. She had first seen it in June 1920, shining above the treetops like a personal aurora borealis, beckoning her north. She hated the city, abhorred being in a place built by man rather than God, but she knew she had no choice. Her feet had carried her straight to Behaimstrasse 72, to bear witness as the raven-haired Frau Jüttner nursed the baby for the first time. Jerusza had seen the baby glowing, even then, a light in the darkness no one knew was coming.

She didn’t want a child; she never had. Perhaps that was why it had taken her so long to act. But nature makes no mistakes, and now, as the sky filled with a cloud of silent blackbirds over the twinkling city, she knew the time had come.

It was easy to climb up the ladder of the modern building’s fire escape, easier still to push open the Jüttners’ unlatched window and slip quietly inside. The child was awake, silently watching, her extraordinary eyes—one twilight blue and one forest green—glimmering in the darkness. Her hair was black as night, her lips the startling red of corn poppies.

“Ikh bin gekimen dir tzu nemen,” Jerusza whispered in Yiddish, a language the girl would not yet know. I have come for you. She was startled to realize that her heart was racing.

She didn’t expect a reply, but the child’s lips parted, and she reached out her left hand, palm upturned, the dove-shaped birthmark shimmering in the darkness. She said something soft, something that a lesser person would have dismissed as the meaningless babble of a little girl, but to Jerusza, it was unmistakable. “Dus zent ir,” said the girl in Yiddish. It is you.

“Yo, dus bin ikh,” Jerusza agreed. And with that, she picked up the baby, who didn’t cry out, and, tucking her close against the brittle curves of her body, climbed out the window and shimmied down the iron rail, her feet hitting the sidewalk without a sound.

From the folds of Jerusza’s cloak, the baby watched soundlessly, her mismatched ocean eyes round, as Berlin vanished behind them and the forest to the north swallowed them whole.

CHAPTER TWO

1928

The girl from Berlin was eight years old when Jerusza first taught her how to kill a man.

Of course Jerusza had discarded the child’s given name as soon as they’d reached the crisp edge of the woods six years earlier. Inge meant “the daughter of a heroic father,” and that was a lie. The child had no parent now but the forest itself.

Furthermore, Jerusza had known, from the moment she first saw the light over Berlin, that the child was to be called Yona, which meant “dove” in Hebrew. She had known it even before she saw the girl’s birthmark, which hadn’t faded with time but had grown stronger, darker, a sign that this child was special, that she was fated for something great.

The right name was vital, and the old woman couldn’t call Yona anything other than what she was. She expected the same in return, of course, a respect for one’s true identity. Jerusza meant “owned inheritance”—a reference to the magic she had received from her own bloodline, and a tribute to being owned by the forest itself—and it was the only thing she allowed Yona to call her. “Mother” meant something different, something that Jerusza never would be, never wanted to be.

“There are hundreds of ways to take a life,” Jerusza told the girl on a fading July afternoon soon after the child’s eighth birthday. “And you must know them all.”

Yona looked up from whittling a tiny wren from a piece of wood. She had taken to carving creatures for company, which Jerusza did not understand, for she herself valued solitude above all else, but it seemed a harmless enough pursuit. Yona’s hair, the color of the deepest starless night, tumbled down her back, rolling over birdlike shoulders. Her eyes—endless and unsettling—were misty with confusion. The sun was low in the sky, and her shadow stretched behind her all the way to the edge of the clearing, as if trying to escape into the trees. “But you’ve always told me that life is precious, that it is God’s gift to man, that it must be protected,” the girl said.

“Yes. But the most important life to protect is your own.” Jerusza flattened her palm and placed the edge of her hand across her own windpipe. “If someone comes for you, a hard blow here, if delivered correctly, can be fatal.”

Yona blinked a few times, her long lashes dusting her cheeks, which were preternaturally pale, always pale, though the sun beat down on them relentlessly. As she set the wooden wren on the ground beside her, her hands shook. “But who would come for me?”

Jerusza stared at the child with disgust. Her head was in the clouds, despite Jerusza’s teachings. “You foolish child!” she snapped. The girl shrank away from her. It was good that the girl was afraid; terrible things were coming. “Your question is the wrong one, as usual. There will come a day when you’ll be glad I have taught you what I know.”

It wasn’t an answer, but the girl wouldn’t cross her. Jerusza was strong as a mountain chamois, clever as a hooded crow, vindictive as a magpie. She had been on the earth for nearly nine decades now, and she knew the girl was frightened by her age and her wisdom. Jerusza liked it that way; the child should be clear that Jerusza was not a mother. She was a teacher, nothing more.

“But, Jerusza, I don’t know if I could take a life,” Yona said at last, her voice small. “How would I live with myself?”

Jerusza snorted. It was hard to believe the girl could still be so naive. “I’ve killed four men and a woman, child. And I live with myself just fine.”

Yona’s eyes widened, but she didn’t speak again until the light had faded from the sky and the day’s lessons had ended. “Who did you kill, Jerusza?” she whispered in the darkness as they lay on their backs on the forest floor beneath a roof of spruce bark they’d built themselves just the week before. They moved every month or two, building a new hut from the gifts the forest gave them, always leaving a crack in their hastily hewn bark ceilings to see the stars when there was no threat of rain. Tonight, the heavens were clear, and Jerusza could see the Little Dipper, the Big Dipper, and Draco, the dragon, crawling across the sky. Life changed all the time, but the stars were ever constant.

“A farmer, two soldiers, a blacksmith, and the woman who murdered my father,” Jerusza replied without looking at Yona. “All would have killed me themselves if I’d given them a chance. You must never give someone that opportunity, Yona. Forget that lesson, and you will die. Now get some rest.”

By the next full moon, Yona knew that a kick just to the right of the base of the spine could puncture a kidney. A horizontal blow with the edge of the hand to the bridge of the nose could crush the facial bones deep into the skull, causing a brain hemorrhage. A hard toe kick to the temple, once a man was down, could swiftly end a life. A quick headlock behind a seated man, combined with a sharp backward jerk, could snap a neck. A knife sliced upward, from wrist to inner elbow along the radial artery, could drain a man of his blood in minutes.

But the universe was about balance, and so for each method of death, Jerusza taught the girl a way to dispense healing, too. Bilberries could restore circulation to a failing heart or resuscitate a dying kidney. Catswort, when ground into a paste, could stop bleeding. Burdock root could remove poison from the bloodstream. Crushed elderberries could bring down a deadly fever.

Life and death. Death and life. Two things that mattered little, for in the end, souls outlived the body and became one with an infinite God. But Yona didn’t understand that, not yet. She didn’t yet know that she had been born for the sake of repairing the world, for the sake of tikkun olam, and that each mitzvah she was called to perform would lift up divine sparks of light.

* * *

If only the forest alone could sustain them, but as the girl grew, she needed clothing, milk to strengthen her bones, shoes so her feet weren’t shredded by the forest floor in the summer or frozen to ice in the winter. When Yona was young, Jerusza sometimes left her alone in the woods for a day and a night, scaring her into staying put with tales of werewolves that ate little girls, while she ventured alone into nearby towns to take the things they needed. But as the girl began to ask more questions, there was no choice but to begin taking her along, to show her the perils of the outside world, to remind her that no one could be trusted.

It was a cold winter’s night in 1931, snow drifting down from a black sky, when Jerusza pulled the wide-eyed child into a town called Grajewo in northeastern Poland. And though Jerusza had explicitly told her to remain silent, Yona couldn’t seem to keep her words in. As they crept through the darkness toward a farmhouse, the girl peppered her with questions: What is that roof made of? Why do the horses sleep in a barn and not in a field? How did they make these roads? What is that on the flag?

Finally, Jerusza whirled on her. “Enough, child! There is nothing here for you, nothing but despair and danger! Yearning for a life you don’t understand is like staring at the sun; your foolishness will destroy you.”

Yona was startled into silence for a time, but after Jerusza had slipped through the back door of the house and reemerged carrying a pair of boots, trousers, and a wool coat that would see Yona through at least a few winters, Yona refused to follow when Jerusza beckoned.

“What is it now?” Jerusza demanded, irritated.

“What are they doing?” Yona pointed through the window of the farmhouse, to where the family was gathered around a table. It was the first night of Hanukkah, and this family was Jewish; it was why Jerusza had chosen this house, for she knew they would be occupied while she took their things. Now the father of the family stood, his face illuminated by the candle burning on the family’s menorah, and though his voice was inaudible, it was clear he was singing, his eyes closed. Jerusza didn’t like Yona’s expression as she watched; it was one of longing and enchantment, and those types of feelings led only to ill-conceived ideas of flight.

“The practice of dullards,” she said finally. “Nothing there for you. Come now.”

Yona still wouldn’t budge. “But they look happy. They are celebrating Hanukkah?”

Of course the girl already kne

w they were. Jerusza carved a menorah each year from wood, simply because her mother had commanded it years before. Hanukkah wasn’t among the most important Jewish holidays, but it celebrated survival, and that was something anyone who lived in the woods could respect. Still, the girl was being foolish. Jerusza narrowed her eyes. “They are repeating words that have likely lost all meaning for them, Yona. Repetition is for people who don’t want to think for themselves, people who have no imagination. How can you find God in moments that have become rote?”

Neither of them said anything for a moment as they continued to watch the family. “But what if in the repetition they find comfort?” Yona eventually asked, her voice small. “What if they find magic?”

“How on earth would repetition be magic?” They still needed to procure a few jugs of milk from the barn, and Jerusza was losing patience.

“Well, God makes the same trees come alive each year, doesn’t he?” Yona said slowly. “He makes the same seasons come and go, the same flowers bloom, the same birds call. And there’s magic in that, isn’t there?”

Jerusza was stunned into silence. The girl had not bested her at her own game before. “Never question me,” she snapped at last. “Now shut up and come along.”

It was inevitable that Yona would begin wondering about the world outside the woods. Jerusza had always known the time would come, and now it was heavy upon her to ensure that when the girl thought of civilization, she regarded it with the proper fear.

Jerusza had been teaching Yona all the languages she knew since she had taken her, and the child could speak fluent Yiddish, Polish, Belorussian, Russian, and German, as well as snippets of French and English. One must know the words of one’s enemies, Jerusza always told her, and she was gratified by the fear she could see in Yona’s eyes.

The Room on Rue Amélie

The Room on Rue Amélie The Winemaker's Wife

The Winemaker's Wife The Forest of Vanishing Stars

The Forest of Vanishing Stars The Book of Lost Names

The Book of Lost Names Italian for Beginners

Italian for Beginners After

After How to Save a Life

How to Save a Life The Blonde Theory

The Blonde Theory The Sweetness of Forgetting

The Sweetness of Forgetting When We Meet Again

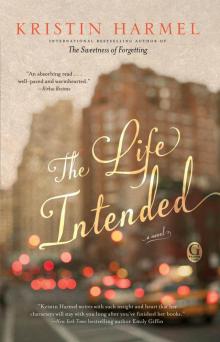

When We Meet Again Life Intended (9781476754178)

Life Intended (9781476754178)