- Home

- Kristin Harmel

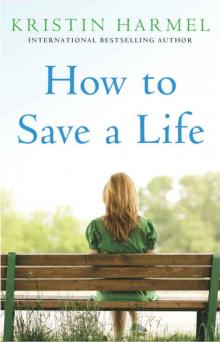

How to Save a Life

How to Save a Life Read online

Thank you for downloading this Pocket Star Books eBook.

* * *

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Pocket Star Books and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

To my father, Rick, who just retired from many years as a pediatric surgeon. He helped save countless lives over the course of a long and wonderful career. I’m proud of you, Dad.

1

THE NOT KNOWING is the worst part.

I’ve seen it a thousand times. Parents clinging to each other as they wait to hear whether their baby will survive. Mothers grasping their children, doing their best at the impossible task of warding off unwelcome news. Teenagers paralyzed by fear as they await word about whether they’ll get the chance to grow up, to fall in love one day, to see old age.

Once you know the answer to your question—Will I live, or will I die?—a form of peace sets in. Now you know. You can move forward—even if the road runs out far before you hoped it would.

I’ve always watched from the outside, moved but detached. It’s a skill you have to possess if you work in a hospital. If you don’t bleed on the inside for your patients, you have no heart. But if you bleed too much, your sanity oozes away at the edges. You learn to walk a fine line between empathizing and reminding yourself that this is the nature of life, and that some lives are tragically shorter than others.

But in all those moments of trying not to drown in the tears of others, I’ve never let myself imagine what it would be like to be in the shoes of a parent or a child waiting for the words that could change everything. After all, if I had imagined, perhaps I would have crumbled. And a nurse can’t crumble, not when it’s her job to keep children whole for as long as possible.

But now it’s my turn to wait.

“BALLOONS?” THE RIGHT corner of Megan’s mouth twitches as she stares at me from her hospital bed. “I mean, really? Balloons? Like balloons are going to make chemo any better?”

I shrug and make a note on her chart. Her blood pressure and temperature are normal. The color is coming back to her cheeks. And she’s now acting like a completely standard fourteen-year-old: secretly happy to have the balloons, but mortified by the attention.

“They’re not supposed to make your chemo better,” I say without looking up. “They’re to celebrate your very last treatment, kiddo.”

“I don’t need balloons.” She crosses her arms over her chest as she glares at me. She’s tiny and frail, and she has at some point this morning put on makeup with a heavy hand, painting her lips an oddly bright pink and smearing on black eyeshadow. She looks ridiculous, and it’s hard to take her seriously as she adds, “And I’m not a kid, Jill.”

“I know.” I put her chart down and manage to keep a straight face. “You’re a world-weary fourteen-year-old. You’ve seen it all. You’ve done it all. And I’m just the old lady who gets the pleasure of your company once a week.”

“You’ll miss me,” she promises. “Don’t tell me you won’t miss me when I get out of here.”

“I don’t know how we’ll survive without your sparkling personality to light up the halls. But we’ll try to find a way, Megan. Now sit back and relax. Dr. Trouba will be along in just a minute.”

“Whatever!” she calls after me as I head out into the hall. “And you’re only sort of old, Jill!”

“Thanks!” I call over my shoulder. I’m pretty sure it’s a compliment.

I make my way down the hall, checking in on Katelyn, a fifteen-year-old with leukemia; Jennifer, an eight-year-old with retinoblastoma; Frankie, a sixteen-year-old with metastatic osteosarcoma; and Shalia, a twelve-year-old with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. All of them have been guests on the pediatric cancer floor of Atlanta Children’s Hospital on and off over the last several months, and all of them are at various stages of fighting for their lives, some more successfully than others. It’s hard, sometimes, to be around them and to continue believing that life works out the way it’s supposed to.

The others will probably make it—that’s the hope, anyhow—but Frankie’s cancer has stormed too many of his organs and taken up permanent residence in his blood. I know that Dr. Trouba, his oncologist, met with Frankie and his parents last week to tell them there’s nothing more they can do except to make Frankie comfortable—the words every parent of a cancer patient must dread.

“It’s not fair,” I murmur as I walk into Logan’s room at the end of the hall. Although we’re not supposed to play favorites, Logan is easily that for me. He’s only ten, but he’s wise beyond his years, probably because he’s had no choice but to grow up far too quickly. When Logan was just ten months old, his mother died of a cocaine overdose. His father had never been in the picture at all, and there were no relatives who wanted to take him in. Logan bounced around in the foster care system for a while, and when he was seven, he was diagnosed with embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. He’d been complaining of an earache for months when his foster parents finally brought him to a pediatrician, who immediately sent him to us. By that time, the tumors in his ear had spread to his nasal passage and his neck. Three years, seven surgeries, and countless rounds of chemo and radiation later, he’s still with us, but his prognosis isn’t good.

The worst part is that he no longer has a foster family. The couple he’d been living with for the six months before his diagnosis said they weren’t equipped to care for a medically fragile child, and now, he’s simply a ward of the state.

“What’s not fair?” Logan asks, arching an eyebrow as I grab his chart from the end of his bed.

“Hmm?” I ask absently as I read over the night nurse’s notes. Logan just had a radiation treatment two days ago, and he’s still rebounding, but I’m glad to see that his blood pressure is stable and that he managed to keep a small meal down last night.

“You said something wasn’t fair, and I was just wondering what you meant.”

“Oh.” I hesitate. “It’s nothing.” After all, Logan’s situation is probably the least fair of all: no family, no chance at a normal life. He should be on a playground somewhere, but instead, he’s spent a third of his short life in the hospital, and his doctors can’t seem to find a way to stop his new tumor growth.

Logan stares at me for a minute, almost as if he’s trying to figure something out. “You know,” he says finally, his voice strangely thick, “sometimes life isn’t as unfair as you think it is.”

I cough and turn away so he won’t see my watery eyes. “Right. Of course, you’re right.”

“You don’t believe that.” He’s tiny for his age, and right now, he seems almost swallowed by the white pillows and sheets of his narrow hospital bed. Yet he’s gazing at me evenly, with the composure of an adult.

“What?”

“You don’t believe that,” he repeats calmly. “You think that life is supposed to deal each of us an equal hand, and that if we don’t all get all the perfect cards right away, we lose.”

“Aren’t you a little young to be making poker references? Even if you do talk like a forty-five-year-old man.”

He smiles. “You’re missing the point.”

I sigh and put his chart down. “No, I’m not. I get what you’re saying. It’s just that sometimes, things don’t work out the way we think they’re going to.”

He nods. “It’s going to be okay, you know.”

“What’s going to be okay?”

“Your doctor’s appointment today.”

I blink a

t him. “How did you know about my doctor’s appointment?”

“It doesn’t matter. What matters is that it’s going to be okay, Jill. It always is.”

Suddenly, my heart is thudding, and my head hurts again. I blink a few times to get ahold of myself. “Did I tell you yesterday that I had a doctor’s appointment?”

“No.”

I take a deep breath. “Okay, Logan, you’re freaking me out a little.”

“Don’t freak out, Jill,” he says. “It’s all going to be fine. Just remember that.”

I’M STILL PUZZLING over Logan’s strange words—and the fact that he’s apparently reading my mind now—as I head out to the nursing station. The waiting room on our floor is quiet, as usual. All of our rooms—or “cancer care suites,” as they’re called by the hospital’s marketing people—have fold-down cots and space for two parents to spend the night, so the only people in the waiting area tend to be extended family members and, occasionally, siblings. Right now, it’s early enough on a weekday that most of those extraneous visitors are at work or in school. I spot a sixty-something couple in the corner and immediately identify them as concerned grandparents, due to their red-rimmed eyes and vacant expressions.

“Please tell me you got laid last night,” Sheila, the head nurse, says as I walk over to the desk to log a few notes. The teary grandmother in the corner looks up.

“Shhh!” I hiss.

“What?” Sheila asks without lowering her voice. “It’s a normal question. You’re a thirty-nine-year-old woman who’s never been married and who probably can’t even remember the last time she had a man in her bed. You getting a bit of action would be a service to society. The whole world would rejoice with you.”

“Sheila!” I glance once again at the woman in the corner, who is staring at us. “It was only a first date.”

“You can’t bone on a first date?”

“Bone?” I repeat. “Seriously?”

“Look,” Sheila replies without missing a beat. “I’m your friend. Your sexually active friend. Your friend who doesn’t understand why you seem to have taken a vow of celibacy.”

“I haven’t taken a vow of celibacy,” I snap. “I just haven’t met the right guy.”

“See?” Sheila says, jotting something down on a chart. “You’re uptight. You wouldn’t be like that if you were getting laid. I guarantee it. So about last night. Tom, was it?”

“Tim,” I correct. “And he was . . . boring.”

“In bed?” she asks sympathetically.

I glare at her. “He was boring at the restaurant. Where we met. For dinner.”

“And why, exactly, was the young, handsome engineer boring?” Sheila asks with a sigh as she turns back to her computer.

“Because all he could talk about was himself.”

“Is that really so bad?”

“Yeah, Sheils, it is. It’s bad because on a first date, you’re supposed to be curious about each other. You’re supposed to be interested in what the other person has to say. And in the best of worlds, you’re supposed to feel some chemistry. You’re not supposed to give an hour-long soliloquy about your own accomplishments.”

“Fair enough,” Sheila says, and for a moment, I think I’ve won the point. But then she adds under her breath, “But you still could have gotten laid.”

I open my mouth to reply, but I’m interrupted by the alarm tone on my cell phone. I roll my eyes, dig it out of my pocket, and swipe away the message on the screen: Dr. Frost, 11 a.m.

“What?” Sheila asks.

“Just that doctor’s appointment across the street. I should be back in an hour.”

“The neurologist,” Sheila murmurs, all trace of her teasing suddenly gone. “I still can’t believe you came in today, Jill. You shouldn’t be here.”

I shrug. I’d gone to a neurologist a few weeks ago because my headaches had gotten bad, and after giving me a CT scan and an MRI, he’d ordered a biopsy. I’d had to spend a night in the hospital afterward, and the recommendation had been to wait a week to return to work, but I hadn’t quite managed that. It’s not easy to stay away from my patients, and besides, I’m sure I’m fine. “You know me,” I say with a shrug. “Besides, the kids would miss me if I skipped too many days of work.” I’m trying to pretend—to both myself and Sheila—that I’m not worried about the appointment today.

“Jill, you’re going to be okay. You know that, right?”

“Of course.” I wave dismissively. “But better safe than sorry, right?”

“Right.”

I walk away, but once I’m inside the elevator, headed for the ground floor, I release the breath I didn’t know I was holding.

I’m so focused on telling myself not to worry as I cross the hospital’s main atrium on the first floor that I collide with a man who’s walking in the opposite direction.

“Oh, geez, I’m so sorry!” I exclaim, stumbling a little.

He reaches out to steady me, his left hand on my right arm. “Are you okay?” he asks.

I nod, shaken. “Totally my fault. I wasn’t paying attention.”

He smiles, and I’m momentarily struck by the way his green eyes seem to catch the sunlight filtering through the glass ceiling ten stories up. “I’m sure it was mine. I was watering.” He holds up a gray garden hose and nods at the sinewy tree with the narrow, winding branches and the dense leaves at the center of the atrium. “I get distracted sometimes.”

I glance at the tree, which I’m pretty sure was a gift from a donor. I’ve loved it since it was first planted here during an expansion of the hospital five or six years ago. A construction crew had installed new columns in the atrium, as well as stone benches encircling the central area, but it was this tree—which replaced an unassuming flower garden—that changed the whole feel of the hospital.

Life. That’s what the tree makes me think of. It’s strong and thriving, always reaching for the sunlight. It provides the perfect message, somehow, for a children’s hospital that treats some of the sickest kids in the state. Just keep living. Just keep reaching for the light.

“Ma’am? Are you okay?” The gardener I’ve crashed into is trying to get my attention, and I blink, embarrassed. He must think I’m a total lunatic.

“I’m sorry. I’m fine.” I refocus on him and am temporarily thrown by the thought that his eyes are the exact same color as the leaves of the great ficus. How have I never noticed him before? “I was just thinking about how this tree is the perfect thing to welcome people to the hospital.”

He raises his eyebrows. “I couldn’t agree more.”

“Well.” Now I’m officially awkward. “Sorry again. And, um, have a good day.”

He laughs. “You too.”

I move past him toward the front entrance to the hospital, and despite the fact that I know better, I find myself turning around, just once, to see if he’s watching me.

He is. And as he smiles again and raises a hand, a silent good-bye, I can feel heat creeping up my neck and into my cheeks. I wave back and hurry on my way, wondering how it’s possible that I felt more in a single awkward interaction with a stranger than I did on my date last night with a perfect-on-paper guy.

“DR. FROST WILL see you now.”

I’ve been waiting for thirty-five minutes for my appointment with Gerald Frost, Atlanta’s most renowned neurologist. I have to remind myself that even when he’d asked for the biopsy, he hadn’t seemed particularly concerned. Then again, there isn’t an ounce of warmth to him; maybe he isn’t capable of concern. “Don’t worry,” a nurse had said to me as I walked out of his office last week, visibly shaking. “He’s just very thorough. He orders follow-ups all the time.”

But now, as one of Dr. Frost’s PAs leads me back to his office instead of an exam room, the fear that I’ve been keeping at bay for the last several days suddenly rears up so p

owerfully that I have to stop and steady myself against the wall.

“Miss Cooper?” the PA says with concern, reaching for my arm to help steady me. I look at her, and in an instant, I know I’m not worrying about nothing. There’s pity in her eyes instead of professional detachment.

“It’s cancer, isn’t it?” I ask her, although it feels implausible. Aside from the headaches, I’m fine.

“I don’t know, Miss Cooper,” she says, looking away. “I’m sure Dr. Frost will explain everything.”

Five minutes later, I’m seated in a starkly decorated office when Dr. Frost, a sixty-something rail-thin man with gray hair, a narrow mustache, and wire-rimmed glasses strides in holding a manila folder. He shakes my hand briskly and settles in behind his desk.

“Miss Cooper, I have a bit of bad news,” he says without any preamble.

It seems he’s waiting for a response, so I manage to croak out, “Yes?” over the lump in my throat.

“I’m afraid that you have an aggressive glioblastoma. It’s actually quite extraordinary that you’ve continued to function without any major side effects aside from the headaches. It has to do with the location of the tumor, but to be honest, I’ve never seen anything like it.”

I stare at him. “You’re telling me I have aggressive brain cancer?”

“I’m afraid so,” he says, refocusing on me as some of the eager excitement seems to drain out of him. “Glioblastomas arise from the star-shaped cells, called astrocytes, which form the supportive structure of the brain. They’re supported by—”

“I know,” I say abruptly. “I’m an oncology nurse. I know what a glioblastoma is. What’s the course of treatment here?”

He blinks at me a few times, as if my direct question has unsettled him. “Miss Cooper, as I was beginning to explain, glioblastomas are generally very malignant and invasive. The median survival rate for these types of tumors in general is just shy of fifteen months.”

The Room on Rue Amélie

The Room on Rue Amélie The Winemaker's Wife

The Winemaker's Wife The Forest of Vanishing Stars

The Forest of Vanishing Stars The Book of Lost Names

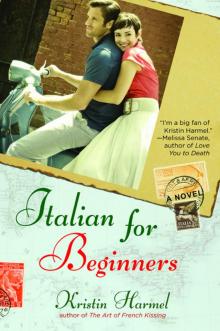

The Book of Lost Names Italian for Beginners

Italian for Beginners After

After How to Save a Life

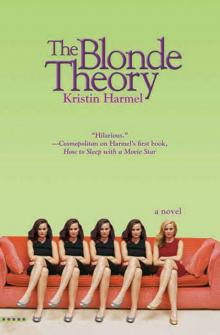

How to Save a Life The Blonde Theory

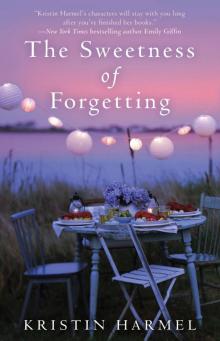

The Blonde Theory The Sweetness of Forgetting

The Sweetness of Forgetting When We Meet Again

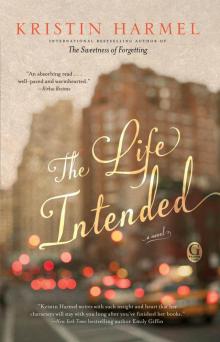

When We Meet Again Life Intended (9781476754178)

Life Intended (9781476754178)