- Home

- Kristin Harmel

The Forest of Vanishing Stars Page 11

The Forest of Vanishing Stars Read online

Page 11

Leib stared at them blankly, fear in his eyes. He was right to be frightened; they were pointing the rifles at him now, asking if he was a Jew. Slowly, her heart hammering, Yona tracked backward so she could approach the men from behind. She had to move slowly to stay silent, but she needed to get to them as quickly as possible before one of them pulled the trigger. “Ja ciabie nie razumieju,” Leib stammered—Belorussian for “I don’t understand”—as he stood in waist-high water, dripping wet. There were many overlaps between the Russian and Belorussian languages, but in Leib’s terror, he was having trouble interpreting words that weren’t immediately familiar. He was in the worst possible situation; the water prevented his escape. He couldn’t simply turn and run and hope that the men missed if they fired at him. He was a cornered target. Yona crept silently closer.

“Ty yevrey?” the smaller man repeated more loudly, his eyes narrowing, and Leib shook his head, clearly frightened.

“Of course he’s a Jew, Vadim,” the large man said in Russian as Leib began to back away. “Look at that nose. Look how dirty he is. He’s probably one of the bastards who’s been stealing from us.”

“Dirty Jew.” The smaller man spat on the ground.

“I think we make him pay. Make an example of him.”

“String him up like a warning, yes, after we put a bullet in his head?”

The men both cackled, and Leib’s eyes darted desperately back and forth from one to the other. It was clear he had little idea what they were saying but realized it was bad. Yona crept closer, close enough that she could smell them. They were both unwashed, stinking of sweat and saline, mud and adrenaline. They were so focused on the boy they were hunting that they didn’t realize they, too, were being hunted.

Slowly, carefully, she reached for the knife that she kept strapped to her ankle, but to her horror, it wasn’t there. She realized in a flash that she had left it beside her reed mat when she had gotten up that morning with panic knotting her insides. She had never done that before, not even when she was a child; she slept with the knife within arm’s reach and then slipped it into its sheath the moment she awoke. Her blood ran cold, but there was no time to curse her terrible timing.

“All right, then. You want to do the honors, Tikhomirov?” the skinny one asked as he continued to leer at Leib.

The big one raised his rifle, pointing it at Leib, who was shaking now. Instantly, Leib raised his hands over his head. Yona had to do something. Her mind spun back to Jerusza’s lessons.

“Shis mikh nisht. Ikh bet aykh!” Leib said in Yiddish, reverting in his panic to the language he’d been speaking in the woods. Don’t shoot me, please.

“He talking that Jew language now?” the big one asked.

The other one laughed. “Think so.”

“Last time he’s ever gonna—”

But the larger man didn’t finish, because Yona had leapt forward, silently, deftly, landing on his upper back, her legs instantly wrapped around his ribs to brace herself.

“What the—?” he began, his voice strangled, but that was all he had the chance to say, because Yona, stabilizing her body with her inner thigh muscles, hoisted herself higher until her head was above his, reached her left arm with lightning speed under his chin, wrapped her left hand around the back of his neck, and jerked up and back as hard as she could. She heard the snap and slid from his back as his body collapsed. She fell instantly behind him, using his body as a shield from the other man, whose face was white with fear as he swung his rifle wildly in her direction.

“Run, Leib!” she called, and as she had predicted, it was enough of a distraction for the confused man, who whirled in the direction of the stream. In the instant before he had turned fully back to her, she struck, first springing forward to gouge his eyes with the sharp index and middle nails of her left hand, and then, the second he tilted his head upward to scream in pain, slicing forward at his unprotected neck with the outer edge of her flattened right hand and thrusting sharply up into the hollow of his throat, crushing his windpipe. He slumped to the ground beside the other man.

Instantly, Yona put her aching right hand to her mouth. What had she done? She had acted on instinct, doing the things Jerusza had made her practice a thousand times, beginning when she was just a little girl. There will come a day when you’ll be glad I have taught you what I know, Jerusza had said. Yona hadn’t believed her then, hadn’t really believed that taking another man’s life could ever be necessary. But now, now she understood. There had been no other way; if she hadn’t acted, they would have killed Leib for no reason at all. Still, that didn’t negate the guilt that surged through her, hot and buzzing. She dropped to her knees beside the two bodies, her hand still over her mouth, tears stinging her eyes. She could hear Leib calling her name, but he sounded very far away.

“I killed them,” she whispered, staring at the bodies. She felt as if she were in a trance, floating above the stream, looking down at the horrific scene. “I took two lives.” She could feel eyes watching her, eyes she knew weren’t really there. “Jerusza,” she murmured. “I killed them.”

“Yona!” Leib’s voice was louder now, and then his hand was on her back, and he was pulling her up. “Yona, we have to go. What if there are others?”

She turned to him, dazed. His face, just inches from hers, looked blurry.

“Yona!” he said again, panic lacing his voice. “Yona!”

She could feel herself coming back to reality, but she still felt as if she were underwater, in the deepest part of Kroman Lake. “I think they were alone. But you’re right. We can’t be sure,” she said dully. She had listened hard to the forest before she struck, and had heard no other human movement. They weren’t with a Soviet unit; they were wandering the forest on their own. Were they trying to make their way home? Did they have wives, children they had hoped to return to? They shouldn’t have been here at all, and now they were dead. “I killed them,” she said more loudly now as Leib’s face finally swam into focus.

“You did it to save me,” Leib said. His eyes were bloodshot, damp, and Yona could see that he was trying hard not to cry.

“I…” Yona looked once more at the bodies of the two men. She shook herself out of it and reached for the rifle lying beside the smaller one. She stood and handed it to Leib. “Go back to the camp. Tell Aleksander what happened. Make sure they’re ready to move.”

He took the weapon uncertainly, his eyes never leaving her face. “What about you?”

“I’ll be along soon. Go, Leib. Run.”

He hesitated only a second more before nodding and dashing into the forest, the gun in his right hand.

The forest had grown quiet; even the birds had stopped singing. After the sound of Leib’s footfalls had faded, Yona knelt once more beside the men. They both had eyes the color of marsh grass, eyes that would never see anything again. She gently closed their eyelids with the palms of her hands, the same hands that had taken their lives, and then, in the silence that surrounded her, she wept. She wept for their families; for the small, frightened group of refugees she had committed herself to helping; for Jerusza; for her own birth parents, whose hearts must have been broken years before when their daughter was stolen.

Finally, she straightened and, grimacing, methodically undressed both men, taking their clothing and boots but leaving their underclothes, for she couldn’t stand to do them the final injustice of baring their bodies to the forest. She bundled their belongings into a pile to take back to the camp. The boots, especially, would come in handy as they moved deeper into the woods, as the cold of the autumn and winter moved in.

And then she rolled both bodies into the shallow stream, the only burial she could give them. The forest would silently absorb them, and by the time anyone found their bones, all traces of her would be long gone. As she watched them sink into the blue, she wiped her eyes. And then, grabbing the clothing and boots, the larger Russian’s gun, and the gill net Leib had left behind, she ran, her feet carry

ing her into the dark of the forest.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

For the next two months, the group moved every week or so, deeper and deeper into the woods, always changing their location and leaving no trace. Yona taught them how to locate water sources below the earth and how to build simple wells. She showed them how to kill, skin, gut, and cook an adder, how to make a meal of May beetle larvae, how to find hedgehogs, frogs, and duck eggs, which were relatively easy picking when the weather was warm. She demonstrated how to trap and bleed small animals, how to field-dress a red deer, how to construct their own beds from reeds, how to lash together branches to make the frame for a temporary shelter, how to pitch their makeshift oak and pine bark roofs at a fifty-degree angle to keep the wind and rain out when the weather threatened. And slowly, they all began to prepare for the coming cold.

She had intended to stay for only a few weeks, until she was sure they’d survive without her. But somehow, the weeks had turned to months, and as the leaves began to change and autumn began to bare her teeth, she was still there.

“You need to find a place to shelter,” she said to Aleksander one day in late September. The sun hung low in the sky, and a cold wind had swept in from the west. The whole group was hiking through a marshy area deep in the woods, hiding their tracks through sometimes ankle-deep water as they looked for a place to sleep for the night.

They were accustomed to moving by now, accustomed to subsisting on meager provisions, accustomed to burning nearly all the calories they took in. They had all grown leaner, stronger, even the children. Daniel had lost his chubby cheeks far too soon and was just as narrow-faced as his older sisters, who often trooped through the forest whispering and holding hands. They were all much too slim, but at least they were healthy, alive. Yona was thankful for that.

“Yes,” Aleksander said, glancing down at Yona with a smile. “It is nearly dark. Let’s look for a clearing on drier land.”

“Yes. But I meant, too, that you need to find a home for the winter, a place that will keep you hidden, safe, and warm until the spring.”

This time, his expression was confused. “But we must keep moving. You said it yourself. It is how we’ve stayed safe.” The week before, on a quick mission into a village on the edge of the forest to get a new pair of spectacles for Moshe, and for Oscher this time, too, Aleksander and Yona had overheard a conversation between two local women who were talking about a small Jewish encampment a kilometer into the forest that the Germans had discovered the week before. Each of the sixteen refugees had been shot on sight, even two little girls. Yona had felt bile rise in her throat, and she’d had to cover her mouth as the women laughed. The chill in her bones hadn’t gone away.

“But there is more to staying alive in the winter than staying hidden,” she said now. They were quiet for a moment as they approached a flat patch of ground hidden in the heart of a cluster of spruce trees. By silent agreement, they stopped and gestured to the group that this would be their spot for the night. Without being asked, Rosalia and Leib, both carrying guns, disappeared to scour the area for signs of human activity.

“But if we stop somewhere for too long, we become easy quarry, don’t we?” Aleksander asked as they set their packs down on the ground and began to collect logs and large sticks for makeshift shelters for the next few days.

“It is more dangerous to face the cold.” Quickly, she pulled her axe from her pack and began to chop down some of the narrow, dead trees nearby. Silently, Aleksander removed his axe, too, and set to work splitting the long, dried logs into poles. They had established a routine since Yona had joined the group and had begun to teach them. Now, together, they could build a hut large enough for six or seven in under three hours, adding a roof of dead oak or live spruce bark when the cold or rain threatened, and Rosalia could do the same. The others had learned to build shelters, too, though they were slower. Yona liked that they had all developed a rhythm, a set of intrinsic responsibilities. It had never been like that with Jerusza; the two of them shared everything that needed to be done, except in the very end. But Yona had learned that a group this large worked best when there was a delineation of duties.

“Besides,” she added after a few minutes as she and Aleksander set up their own small, individual lean-tos, just beside each other, as had become their custom. He was almost always the first person she saw when she woke in the morning, and she realized she liked that very much. “We are deep enough in the forest now that no one will find you once the snow begins to fall.” On the other side of the clearing, Sulia—who usually shared a shelter with Luba and Rosalia—watched them as she lashed together her own gathered branches.

“But won’t we leave traces in the snow?” Aleksander asked. “We’ll be more obvious if they come looking.”

“You will build shelters into the earth, both for warmth and to hide. And you will move about only when the snow is falling and will cover your tracks. The nights are long and the days are gray. It’s easier to disappear in the cold.”

Aleksander didn’t say anything as he finished lashing his shelter and covering the roof with bark.

“When you speak of the winter, Yona, you never use the word we,” Aleksander said finally, turning his gaze back to her. “Are you leaving?”

She was silent for a long time, for she didn’t know the right answer. “That was always the plan, wasn’t it? That I would stay only until you didn’t need me anymore?”

Aleksander waited until she looked him in the eye. “We still need you, Yona,” he said, his voice low.

“Aleksander—”

“Please. Don’t leave.”

“You’ll survive without me.”

“But I think I would miss you far too much.” He cleared his throat. “We all would, I mean. You are one of us now. Stay—unless you don’t want to.”

She held his gaze for a long time, and in it, she saw a future she had never imagined for herself, a future filled with laughter and friendship instead of silence and loneliness. Maybe even a future filled with love. “I do,” she said softly. “I do want to.” But even as she said it, the wind whipped up, and she could hear it whispering to her, hissing a warning.

Two days later, they’d found a spot deep in the woods, a two-hour hike from the closest stream. Yona spent an additional day searching for an underground water source before digging a shallow well and returning to tell the group that they’d found their spot for the winter. No one argued.

They started with bark-covered huts for shelter, but by the second day, they were all burrowing into the earth with makeshift shovels, everyone but the children. The girls were running around the outskirts of the clearing, pretending to be wood fairies, while Daniel giggled at them from his bed of reeds. Their laughter made Yona smile, even as her muscles burned. This was what they were saving—a future of smiles for these three innocent children, maybe even for the children Pessia, Leah, and Daniel would have themselves someday. For the millionth time, Yona wondered at a world that would allow lives like theirs to be violently snuffed out.

By the end of the next week, following Yona’s instructions, the group had finished two large zemliankas and a much smaller one. Unlike the temporary huts they had been constructing over the last few months, designed to be assembled and disassembled quickly, these were solid, permanent, protected. They were dug deep into the ground, with walls made of five-inch logs, wooden floors, and underground ceilings covered in earth and supported by log beams, each with a narrow stairway to the entrance aboveground. Now, before the first snowfall, the doors to the shelters were visible, but once the forest was under a blanket of snow, they would disappear. It would take the group a few more weeks to build mud-brick stoves and chimneys for warmth, and Yona would show them how; she had done it each year of her life with Jerusza as they prepared for the winter freeze.

The group also built a smaller, separate underground bunker for food storage, which Yona was eager to start filling before the cold made gathering harder,

and a small latrine. In the end, in the space of two weeks, they all had real, semipermanent homes for the first time in years.

While Leib, Aleksander, and Moshe hunted and fished, the women gathered plants and berries, and Leon and Oscher tended a large smoker, Yona ventured out each day into the forest, gathering herbs to dry. Soon the ground would be frozen solid, and nature’s medicines would be underground until the spring.

When she’d lived with Jerusza, they had done this each year, drying the plants they gathered, pulverizing some for teas and poultices and keeping others whole. But for a group of fifteen people—of all different ages—the need was greater. So Yona gathered yarrow, wormwood, chicory, and chamomile. She pulled leaves of dziurawiec for wound care, black lilac and yarrow for fevers, coltsfoot for coughs, nettle leaves for muscle weakness, rosemary for heart ailments, horsetail tips for swelling, and comfrey to treat broken bones and arthritis. By the time the air tasted like snow, she had assembled a whole arsenal of dried or mashed herbs that would take them through the winter.

On a morning early in December, Yona awoke before dawn, and, even from her nest beneath the earth, she could feel the change in the air. She pulled on her wool coat and made her way aboveground, where snowflakes were falling, clinging to the dirt for only a second or two before disappearing forever into the earth. Soon the snow would begin to stick, but for the first few minutes, it was as if the sky and the ground met, becoming one.

She tilted her head up and felt the flakes kiss her cheeks. The season’s first snowfall in the depths of the forest was always magical, and though Yona had lived through nearly two dozen winters, the thrill of it never faded. Though she knew the sugar-delicate flakes were the harbinger of coming danger, of a winter that would test the resilience of all of them, there was no denying their beauty as they drifted down gently from a silent sky.

“Yona.” She heard Aleksander’s voice behind her, and she turned, startled out of her reverie. He was standing in front of the entrance to the larger zemlianka, watching her.

The Room on Rue Amélie

The Room on Rue Amélie The Winemaker's Wife

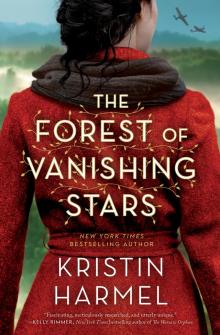

The Winemaker's Wife The Forest of Vanishing Stars

The Forest of Vanishing Stars The Book of Lost Names

The Book of Lost Names Italian for Beginners

Italian for Beginners After

After How to Save a Life

How to Save a Life The Blonde Theory

The Blonde Theory The Sweetness of Forgetting

The Sweetness of Forgetting When We Meet Again

When We Meet Again Life Intended (9781476754178)

Life Intended (9781476754178)