- Home

- Kristin Harmel

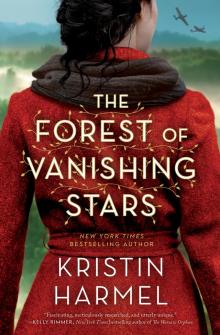

The Forest of Vanishing Stars Page 17

The Forest of Vanishing Stars Read online

Page 17

* * *

Jerusza had always taught Yona to move east when there was trouble, always flying toward the sunrise, never the sunset. Always move toward the beginning of the day, not the end. The old woman’s words rang now in Yona’s ears as she fled in the wrong direction, wanting only to be free of Aleksander. She needed to clear her head, to run from the guilt of abandoning the group, even if some no longer wanted her there.

She had done what she could for them, and she’d left them with the tools they’d need to survive. They might well have made it through the winter without her anyhow; they didn’t know the forest as well as she, but they were all smart, resourceful. It was likely they could have figured out on their own how to eat, how to shelter, how to hide themselves from the Germans. Maybe she had meant nothing to them at all.

Besides, though she understood now that Aleksander was not to be trusted, he had led the group well, had made good decisions about their survival. Zus had become a leader, too, and together, they understood the things the forest would require of them.

She wasn’t a savior. How had she let herself believe that she held their fate in her hands? That had been foolish, selfish. They didn’t need her, no matter what Zus had said. So why did his voice echo in her ear now? Stay, Yona. Please.

For three weeks, Yona meandered through the forest, venturing out now and again on the southwestern edge of the trees, hoping to catch a glimpse of other people just to assuage her loneliness. She could hardly believe that after a lifetime with only Jerusza’s company, she no longer knew how to be by herself. She missed the feeling of thinking she mattered, even a small bit, to others. She missed seeing others’ smiles, hearing laughter, sharing meals. She even missed the comforting heat of Aleksander beside her at night. She hadn’t realized that once one opened the door to one’s heart, it was impossible to fully close it again. At night, in those hazy moments before she fell asleep in the hollows of lonesome old trees, she often heard the voices of the children—Pessia, Leah, Daniel, Jakub, and Adam. She missed them most, for they were the most in need of her protection. They were the ones who haunted her when she tried to rest.

Twice she considered turning back, but she forced herself to keep moving, though her pace was slow. Alone, she was usually swift as an eagle, but she found herself lingering, staying within a few days’ walk of the group, just in case. But she couldn’t live in this limbo forever. She had to put some distance between herself and the group so she didn’t turn around, didn’t follow the heartbeats that drew her back to the east.

Jerusza’s words were haunting her now, too, as she continued west, the direction from which she’d originally come, so long ago. Behaimstrasse 72 in Berlin. Siegfried and Alwine Jüttner. Her parents. Jerusza had said she mustn’t return to them, but what if the old woman had been wrong all along, terribly wrong, and had taken Yona from the life she was meant to have? What if finding her parents now could banish the crushing sense of loneliness that threatened to overtake her?

But the thought was foolish, and Yona knew it. Europe was at war. She couldn’t simply cross through Poland and waltz over the German border, could she? And who knew if twenty-one years after their child had been taken from them, the Jüttners were still there. What if they had moved, or worse, died? But when Yona had asked Jerusza on her deathbed whether she would see them again, Jerusza hadn’t denied it; she had merely delivered another confusing proclamation. The universe delivers opportunities for life and death all the time. But what did that mean? Was finding her parents an opportunity for life? Was that why her feet continued to carry her west? She felt as if she were being swept across the continent by forces greater than herself, and for once, still swimming in grief, she let the current take her.

She was moving toward the Białowieża Forest, the Forest of the White Tower, where she had lived for a time with Jerusza, the forest where she’d met a young man named Marcin almost a decade ago, startling her out of her isolation. It was a place that felt like home to her, and now she longed for its embrace—but that meant she had to cross a land that was far more populated with both villagers and soldiers than it had been when she and Jerusza last traversed it years before. She knew how to disappear in public, though, not by looking down but by walking with her head held high, meeting people’s eyes for fleeting instants instead of shying away from their gaze. It made her look as though she had nothing to fear, nothing to hide, but she also knew to avoid the kind of extended eye contact that made bears, wolves, and men feel as if she was an aggressor.

She washed herself in a brook, scrubbing her face pink, scraping the dirt from her knuckles and nails, lathering her hair with Saponaria flowers and rinsing it until it gleamed. She changed from her familiar shirt and trousers into the dress that lived at the bottom of her pack, the one she used only as an extra layer in the depths of winter. Jerusza had stolen it for her years before, telling her she must always keep it with her, for if she needed to venture into a village, her rugged shirt and torn trousers would immediately mark her as suspicious. Since Yona would have to slip through a few dots of civilization before reaching the safety of the woods to the west, she would need to look as if she belonged.

She was just passing the outskirts of a large village she didn’t know, grateful that she’d almost reached another cluster of trees, when she heard a burst of machine-gun fire, a scream, and then—after a congress of startled crows had lifted off, darting away from the danger overheard—only cold, eerie silence. Yona froze.

Suddenly, there was movement up ahead, near an old church on the edge of the town. It was enough to snap Yona out of it, and at last she scrambled into a thatch of trees up a hill, hiding behind a large oak as a woman hurried into view. It was a nun, wearing a black habit, but the distinctive white yoke and hood were stained with blood. She was carrying a small child, a little girl with long blond ringlets whose bare feet dangled lifelessly from the nun’s arms.

The nun was crying as she approached a small house behind the church. “Father Tomasz! Father Tomasz!” she called. “Please, are you there?” The woman couldn’t knock on the door, for the child hung heavy in her arms, but surely if there had been someone inside, he would have heard her. No one came, and the nun’s moan of despair a moment later shook Yona to her core. She dug her fingernails into the tree, waiting. If the little girl was dead, there was nothing she could do. But if she was still alive…

And then, suddenly the girl stirred, and Yona was halfway down the small hill before she could reconsider. The nun turned at the sound of footsteps and looked startled, but she must have seen something in Yona’s eyes that spoke silent volumes, because she held Yona’s gaze and said simply, in Belorussian, “She has been shot. You are someone who can help? I don’t know how to save her, but if we don’t do something, she will die.”

“I will do what I can,” Yona said, and the nun nodded once, then handed the limp child to Yona and gestured for her to follow her to the church several meters from the house. Together they swept through the back door into a darkened vestibule. The nun lit a candle, and then another as Yona laid the girl gently on the floor and put a hand to her neck. She still had a pulse, a strong one, and Yona exhaled in relief. “Water,” she said, turning to the nun. “I need water, and alcohol for the wound, if you have it. And yarrow to help clot her blood. Does yarrow grow near here?”

“One of the sisters keeps a small basket of medicinal herbs. I will see what she has.” The nun stood, wiping the blood from her hands onto the cloth of her habit, where it seemed to disappear, taken by God. “Please. Do not let her die.”

“I will not.” Yona didn’t know what made her issue a promise she might not be able to keep, but it seemed to reassure the nun, who nodded and hurried away.

Yona turned her attention back to the girl, whose lips were moving, as if she was trying to say something, though she was still unconscious. Her face was white, and when Yona put a hand to her forehead, it was clammy and cool, covered in a sheen of perspirat

ion. Yona unbuttoned the child’s dress and saw the wound where the bullet had entered her tiny body, tearing through her just below the collarbone and under her left shoulder. Another two or three centimeters to the right and it would have shredded her heart.

As gently as possible, Yona lifted the girl slightly, bending her own head to see the child’s back. There was an exit wound, too, which was a blessing, but she was bleeding heavily. Yona laid her back down and the girl groaned, her face constricting.

The nun was back within a few minutes with everything Yona had asked for, and without a word, Yona quickly set to work, first disinfecting the wound with the vodka the nun handed her—encouraged when the child flinched—and then spreading a paste from hastily ground yarrow on both the little girl’s chest and back. Gradually, the bleeding slowed, and when Yona put her cheek on the child’s chest, she could hear a strong heartbeat and steady breath. Sighing, she straightened up and met the gaze of the worried nun.

“She is still alive,” the nun said, and Yona could see that the woman was crying.

Yona nodded. “Someone should get her parents.”

“Her parents are dead.” She wiped her eyes, but new tears sprang up in place of the vanished ones. “The Germans shot them. They thought they’d killed her, too.”

Yona could feel her heart constrict in her chest. “They are Jewish?”

The nun shook her head. “They thought her parents were communists.” Her tears were falling more quickly now. “The Jews of our town have been mostly taken away—taken away or murdered.” She put both palms to her cheeks and drew a deep breath. Her eyes—a watery, crystal blue, framed by laugh lines that hadn’t been used in a while—locked on Yona’s. “Some of those soldiers probably believe themselves to be good Christians. But shooting an innocent family… How could anyone believe that God approves of that? I’ve been searching my soul about it, and I’m no closer to an answer than I was the day they arrived.”

“I’m—I’m not Christian,” Yona blurted out, and then immediately felt foolish, exposed. Why say such a thing? It was just that she couldn’t bear the way the woman was looking at her, her eyes begging for an explanation.

The nun nodded slowly. “Jewish, then?” Her tone was even, and Yona couldn’t tell what she was thinking.

Over a long few seconds of weighted silence, Yona considered the question. In the woods, though she had felt as if she didn’t belong, she had also felt a deep kinship with the people who believed the same things she did, even if she wasn’t always familiar with their customs. “Yes, I think I am,” she whispered, though it was surely foolish to admit such a thing, even to a nun who seemed kind. It was impossible to know whom to trust anymore, but she had to trust God, didn’t she? And she couldn’t betray him with a lie, not in a church where people came to worship him.

Yona waited for the nun’s expression to change in judgment, but instead, she looked relieved. “Good. So you believe in God, then.”

Yona blinked a few times. “Of course I do.”

“Well, that’s what matters, don’t you think?” The nun sighed and looked down at the girl. “I believe the things I believe, but we all come to God in different ways, don’t we? This, though, this is not the way.”

Just then, the girl stirred. Her eyelids fluttered, and then she blinked several times, looking back and forth between Yona and the nun, the fear in her expression deepening each time her eyes opened again. “Who are you?” she asked in Belorussian, her voice barely a whisper as her gaze settled on Yona.

“My name is Yona. And this is Sister—”

“Sister Maria Andrzeja,” the nun filled in softly.

“We are here to help you,” Yona said. “What is your name?”

The child looked from Yona to the nun and back again, and some of the terror left her expression. “Anka,” she whispered.

“Anka,” Yona said, hearing the tremor in her own voice. “It’s important that you stay very still for now. You are hurt, and we are helping you.”

The girl looked down at her chest, and her eyes widened when she saw all the blood. She raised her gaze back to Yona. “My mother and father?”

Yona couldn’t speak over the sudden lump in her throat, and so, with her eyes never leaving the girl’s, she shook her head.

Anka blinked a few times, absorbing the news, and then her face crumpled and she began to cry. “I saw them, you know, when my eyes were closed. My mother, she was saying goodbye to me.”

Yona choked on her own stifled sob and had to turn away for a second to gather herself. Sister Maria Andrzeja moved in beside her to hold the child’s hand. “You are here with us now, and we will protect you.”

“But where is here?”

“The Church of Saint Helena,” the nun replied. “Here we help people in need.”

“But I am not Catholic,” Anka whispered. “My father, he did not believe in God.”

“But God believes in you, my dear,” Sister Maria Andrzeja replied immediately. She looked up and held Yona’s gaze. “And that makes us all the same, all over the world.”

* * *

Later, with the girl hidden in a small room beneath the church, finally asleep though she whimpered while she dreamed, Yona sat on a pew in the church’s main room, staring up at the gold crucifix above the altar. She had never been inside a church before, never seen such a detailed depiction of the Jew who was said to have sacrificed his life on the cross for the world’s salvation. As she studied him now, in candlelit darkness, she felt a great sweep of sadness. Was faith futile in times like these? Where was God in all of this, in this world where people starved to death or perished at the hands of cruel and heartless men? Where was God when neighbors turned against each other?

“It is easy to question our faith,” Sister Maria Andrzeja said, coming to sit beside Yona. She had changed her clothing, and now the collar that framed her face was a stark white, all traces of the little girl’s blood erased. “And much more difficult to maintain it.”

“I don’t understand how God can let these things happen,” Yona whispered, looking at the nun and then back at the altar, where the gilded Jesus watched in silence. “All of this. This heartache. This death. This suffering. The woman who raised me taught me never to question God, but sometimes lately, I can’t help myself.”

Sister Maria Andrzeja was quiet for a while. “Throughout all of mankind’s history, God has tested us, has tested our faith. Do you know the story of Job?”

Yona nodded.

“Then you know that God protected Job, and Job prospered. Job was a good man; the Old Testament describes him as blameless and upright, a man who feared God and shunned evil. Satan came to God, and God gave Satan permission to test Job, to test his faith, by taking everything from him but his own life. And so Satan did, taking all Job held dear. Job cursed the day of his own birth, but he never cursed God. He did not understand why God was testing him, but he still believed in the Almighty.”

Yona shook her head in frustration. “But at the end of Job’s life, God restored everything. That is not happening here. God is letting innocent people die, so many of them, at the hands of evil. The little girl in the basement, what did she do to anyone? Why would God let so many people like her be tested?”

“Do not abandon faith, my child.” The nun’s eyes were a deep well of sorrow. “We can only pray to be his servants, to do what we can to ease the suffering and to save the innocent.”

Yona looked down. “What if I am failing in that?” She thought of the way fate had put her in the path of the refugees in the forest. God had given her a chance to help them, and at first, she had answered the call. Had she failed God by turning her back now?

“You can only do your part. You can do your best to strike a match in the darkness, to light the way. God is with you, always, and he sees what’s in your heart.” The nun folded her hands over Yona’s. “Today you saved that child’s life. That was God working through you. Tomorrow you might help someone els

e. As long as you are doing good, you are doing God’s work. You are making a difference.”

“Whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world,” Yona murmured to herself.

“The Talmud.”

Yona looked up in surprise. “You know the Talmud?”

Sister Maria Andrzeja smiled slightly. “Those of us who seek spend a lifetime trying to find God, to know him, to understand him. Perhaps we can hear him where we least expect. But we must always listen. We must never turn our backs.”

Yona felt tears in her eyes as she nodded. The nun, solid in her Catholic faith, was as spiritually far from Jerusza as one could get. And yet they’d both been on the same journey to understanding.

“I don’t know where you’re coming from, or where you’re going,” the nun continued after a moment. “But there is a room in the attic. Won’t you stay for the night, at least?”

Yona’s heart skipped. “Oh, I couldn’t possibly—”

“It is probably dangerous to ask you to remain here. But it is not for my benefit. Or for yours. It is for the child. I may need your help.”

Yona bowed her head. The nun was right. She couldn’t leave without making sure the girl had a chance to live. “Yes, of course.”

“Good.” The nun stood and patted Yona’s hand. “Do not be afraid to ask your questions. But you must always be sure your heart is open to hear the answers.”

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Yona slept fitfully on the wooden floor of the church’s small attic, somewhere beneath the steeple and the cross that stood above it. It was the first time in more than two decades that she’d spent the night anywhere but the woods, and the stillness of the air and the quiet of the old building made her uneasy. Twice she stood up to leave, but each time, she could smell Anka’s blood on her own clothes, and she reluctantly lay back down.

The Room on Rue Amélie

The Room on Rue Amélie The Winemaker's Wife

The Winemaker's Wife The Forest of Vanishing Stars

The Forest of Vanishing Stars The Book of Lost Names

The Book of Lost Names Italian for Beginners

Italian for Beginners After

After How to Save a Life

How to Save a Life The Blonde Theory

The Blonde Theory The Sweetness of Forgetting

The Sweetness of Forgetting When We Meet Again

When We Meet Again Life Intended (9781476754178)

Life Intended (9781476754178)